Understanding the Acoustics Behind Unified Choral Sound

Every choral director knows the moment when the choir suddenly locks in. The tone blooms, pitch steadies, and the sound seems to float effortlessly through the room. The singers may not be any louder, but the resonance is radiant and unified. That magical moment is making the most of natural acoustics. When singers match vowels precisely, they are actually tuning their formants, the resonant frequencies of the vocal tract, so that their voices reinforce each other acoustically.

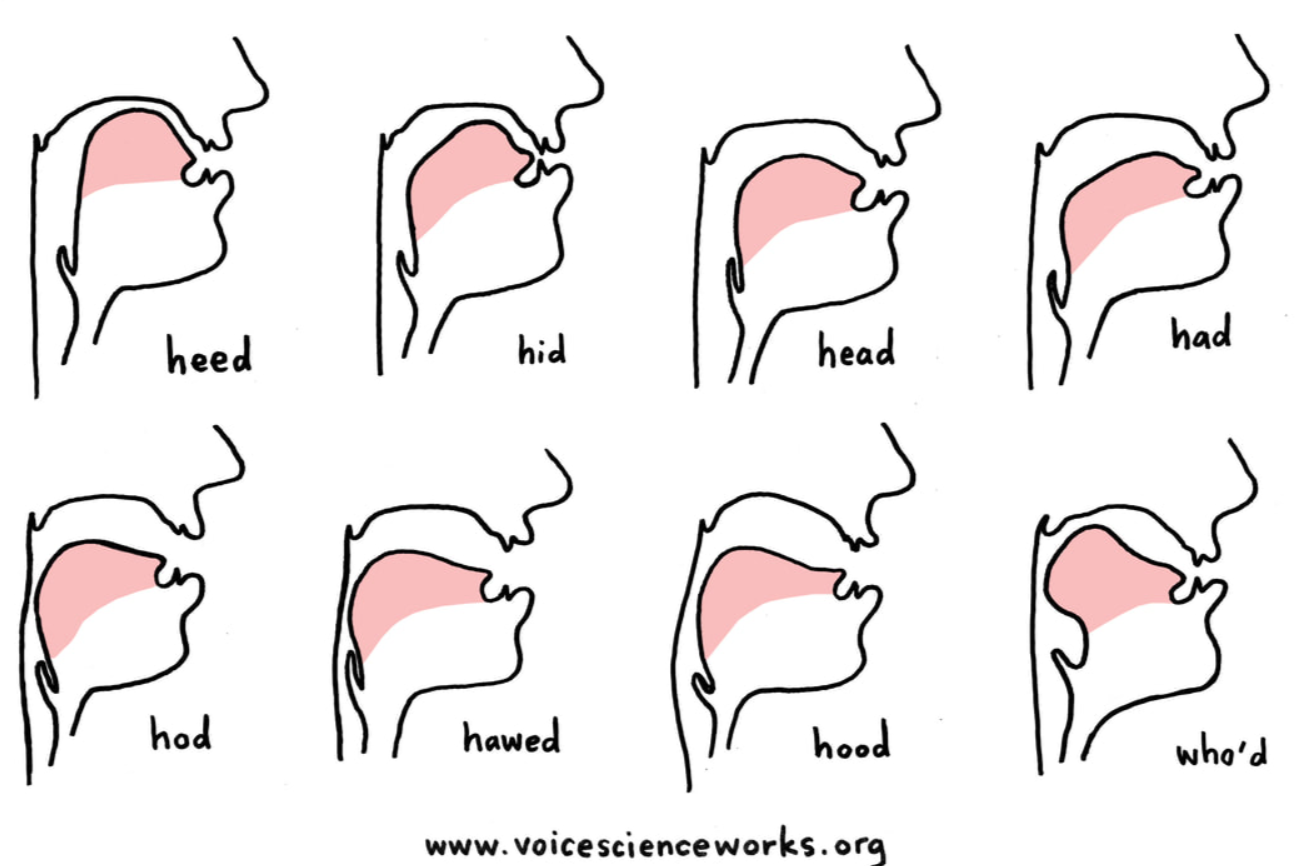

Vowels Are Resonances: Every sung vowel, “ah, eh, ee, oh, oo,” is defined by a unique pattern of resonances called formants. These resonances amplify specific overtones (harmonics) of the sung pitch, shaping both vowel identity and tone color. When a vowel’s formants align well with the harmonics of the sung note, choral sound becomes naturally amplified, the voice feels easier, and singing requires less effort.

What Happens When Choirs Match Vowels: When all singers shape their vowels alike, their individual formants align in roughly the same frequency regions, which means that each singer’s harmonics boost together, a phenomenon known as acoustic coupling (Nix & Karna, 2012). The result is powerful:

Shared resonance: overlapping formants reinforce each other, producing a unified tone color.

Enhanced overtones: matching boosts specific harmonics, creating the much-desired choral ring.

Improved intonation: resonance alignment stabilizes pitch perception, so tuning locks in.

Ease of production: singers expend less muscular effort because resonance does the work.

As Nix and Karna (2012) explain, “the first step is to get all singers within the section to agree upon the vowel in question,” because only when vowels are acoustically unified can resonance, and therefore pitch and blend, be truly shared (p. 15).

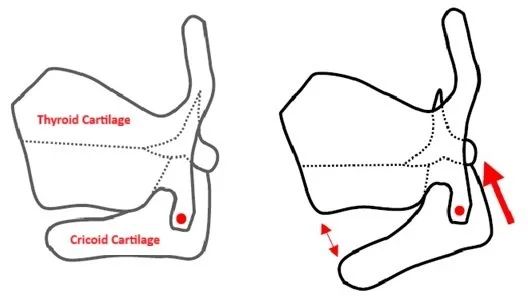

F₁ (first formant) changes mainly with jaw and tongue height. Open vowels like “ah” raise F₁; closed vowels like ee lower it.

F₂ (second formant) changes mostly with tongue advancement. Forward vowels (ee) raise F₂; back vowels (oo) lower it.

Higher formants (F₃–F₅) influence “ring,” “brilliance,” and the singer’s formant cluster that gives voices their carrying power (Bozeman, 2013; Titze, 2008).

When Vowels Differ, Energy Scatters: If some choir members sing a vowel with a wider mouth (raising F₁) and other sings it more closed (lowering F₁), their amplified harmonics no longer align. Instead of reinforcing one another, some overtones cancel each other out, resulting in a less focused, less resonant sound and often unstable intonation. Thus, a diction issue leads to an acoustic tuning problem, directly affecting harmonic reinforcement and perceived pitch.

Matched Vowels Feel Better! When an ensemble aligns vowel resonance, singers often describe the sensation as less effortful and more ringing. The feeling of ease occurs because efficient resonance allows the vocal folds to vibrate with optimal airflow and minimal resistance. The resonance itself supports the tone, reducing unnecessary physical effort (Bozeman, 2022; Titze, 2008).

Practical Strategies for Choirs

Agree on a vowel target. Have each section bodymap what every vowel looks, sounds, and feels like.

Use the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). IPA helps choirs identify the target vowel and make subtle, shared vowel adjustments.

Encourage vowel consistency across pitch. Higher notes may require slightly more open or rounded vowels to maintain resonance alignment.

Listen for the “ring.” When vowels align, the overtones bloom, and the choir’s sound becomes self-reinforcing.

As Nix & Karna (2012) remind directors, effective vowel unification is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Men, women, children, and even different voice types, modify vowels differently to achieve balanced resonance (pp. 16–17). The goal is not to create identical mouth shapes, but rather to achieve shared acoustic function.

The Science Behind the Magic

Physicist and voice scientist Ingo Titze (2008) demonstrated that when harmonics and formants align, sound energy increases exponentially. Bozeman (2013) adds that singers can learn to feel these acoustic conditions as sensations of vibrancy or “ring.” When every singer in a choir tunes their resonance this way, their individual voices merge into one vibrant, efficient sound, a hallmark of great choral singing.

When vowels match, resonance aligns. When resonance aligns, harmonics reinforce.

When harmonics reinforce, the choir's sound rings, and intonation locks.

It is artistry and physics, one of the most beautiful intersections of science and song.

Institute for Healthy Singing & Voice Research

Jamea J. Sale, PhD

Director, Institute for Healthy Singing & Voice Research

Sing for a Lifetime

JSale@HealthySinging.org

________________________________________

References

Bozeman, K. W. (2013). Practical vocal acoustics: Pedagogic applications for teachers and singers. Pendragon Press.

Bozeman, K. W. (2022). Kinesthetic voice pedagogy: Motivating acoustic efficiency (2nd ed.). Inside View Press.

Nix, J., & Karna, D. R. (2012). Vowel and consonant modification for choirs. In D. R. Karna (Ed.), The use of the International Phonetic Alphabet in the choral rehearsal (pp. 11–26). Scarecrow Press.

Titze, I. R. (2008). Principles of voice production (2nd ed.). National Center for Voice and Speech.

Miller, D. G. (2008). Resonance in singing: Voice building through acoustic feedback. Inside View Press.

Doscher, B. M. (1994). The functional unity of the singing voice (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press.