Rethinking Posture for Singing: From Alignment to Adaptability

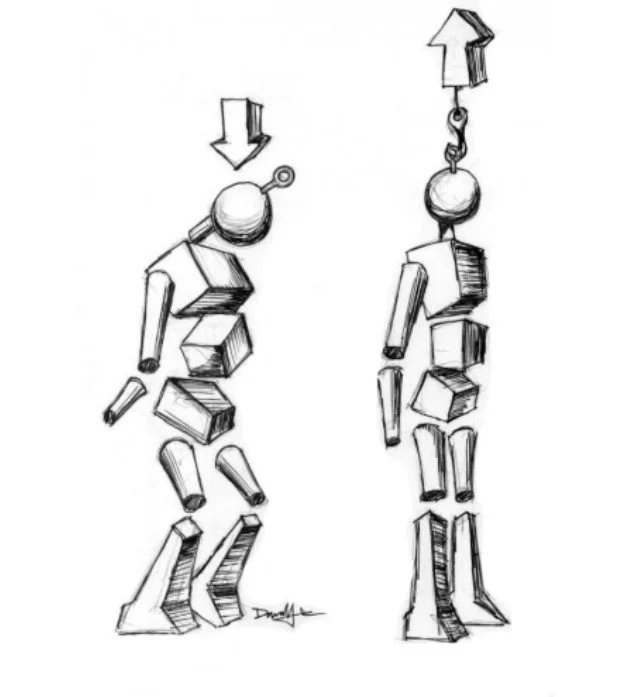

If you’ve ever been told to “stand up straight and tall” while singing, you’re not alone. But research suggests that what matters most is not holding a perfect position. It’s the body’s ability to adapt with balance, freedom, and awareness.

What the Latest Research Shows A 2025 pilot study led by Adrián Castillo-Allendes and colleagues explored how different body postures affect voice function in trained singers. Using 3D motion capture and surface electromyography (sEMG), the researchers measured muscle activity and airflow during sustained and staccato vocal tasks in four postures: upright, modified upright, leaning (“Tower of Pisa”), and upright on an unstable surface (Castillo-Allendes et al., 2025). Surprisingly, the study found no significant differences in muscle activation or voice aerodynamics among these postures. In other words, skilled singers maintained consistent voice output across all conditions even when balancing on an unstable surface. The only measurable difference was in pitch stability: singers produced slightly more pitch variation when standing on an unstable base. This suggests that experienced singers automatically regulate posture to maintain efficient vocal function—a kind of kinesthetic intelligence built through years of training.

Why Posture Still Matters, Especially for Beginners and Recovering Voices Before you toss out your mirror checks and body alignment cues, it’s important to recognize who wasn’t part of the study: singers with postural imbalance, excess tension, or vocal injury. The researchers themselves noted that posture modification may have greater effects in untrained or dysphonic voices, where habitual tension patterns or imbalances interfere with natural breath support and phonation (Castillo-Allendes et al., 2025). For these singers, the goal isn’t rigid “good posture” but recalibration. McKinney (1994) described efficient posture as “freedom from unnecessary tension,” and Feldenkrais (1977) emphasized uprightness derived from “dynamic equilibrium” rather than holding the body erect. These principles remind us that the spine’s curves, head balance, and rib cage mobility all contribute to both vocal efficiency and comfort.

Voice therapy approaches such as the proprioceptive-elastic (PROEL) method and Alexander Technique echo this idea, promoting awareness of movement rather than static positioning (Lucchini et al., 2018; Arboleda & Frederick, 2008). By improving postural awareness, singers can unlock more efficient breath use, reduce compensatory tension, and restore natural vocal resonance.

The Mind-Body Connection: Posture as Confidence Physical alignment also influences emotional state and performance readiness. In my own 2021 study (Sale, unpublished), collegiate singers who assumed expansive, “high-power” poses not only reported greater confidence but also performed sight-singing tasks more accurately than when using low-power, contracted poses. These findings parallel broader psychological research showing that upright, open postures enhance positive mood, focus, and self-efficacy (Briñol et al., 2009; Cuddy et al., 2015). For singers, posture therefore functions on two levels: it aligns the body for efficient breathing and phonation, and it primes the nervous system for confidence and expressive presence. When singers embody freedom, their sound—and spirit—reflect it.

Putting It into Practice

- Check your balance. Instead of “standing up straight,” think of allowing your body to stack naturally over your feet, feeling buoyant rather than braced.

- Use movement. Gentle swaying, arm circles, or reaching movements while singing can help release tension and reawaken kinesthetic awareness.

- Pair posture awareness with breath awareness. Notice how the ribs, abdomen, and pelvic floor move together in breathing. Efficient posture allows this coordination without strain.

- Prime confidence. Before a performance, take a moment to assume an open, grounded stance: shoulders released, sternum high, chest open, eyes level. Your body cues your brain toward assurance.

Closing Thought Trained singers can adjust dynamically to physical demands because they’ve learned to coordinate breath, alignment, and awareness as a single system. For others, posture retraining offers a pathway to restore that integration, supporting both the physiology and psychology of expressive, effortless sound.

Institute for Healthy Singing & Voice Research

Jamea J. Sale, PhD

Director, Institute for Healthy Singing & Voice Research

Sing for a Lifetime

JSale@HealthySinging.org

References

Arboleda, B. M. W., & Frederick, A. L. (2008). Considerations for maintenance of postural alignment for voice production. Journal of Voice, 22(1), 90–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2006.08.001

Briñol, P., Petty, R. E., & Wagner, B. (2009). Body posture effects on self-evaluation: A self-validation approach. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(6), 1053–1064. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.607

Castillo-Allendes, A., Delgado-Bravo, M., Reyes Ponce, Á., & Hunter, E. J. (2025). Muscle activity and aerodynamic voice changes at different body postures: A pilot study. Journal of Voice, 39(2), 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2022.09.024

Cuddy, A. J. C., Wilmuth, C. A., Yap, A. J., & Carney, D. R. (2015). Preparatory power posing affects nonverbal presence and job interview performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(4), 1286–1295. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038543

Feldenkrais, M. (1977). Awareness through movement. New York: Harper and Row.

Lucchini, E., Ricci Maccarini, A., Bissoni, E., et al. (2018). Voice improvement in patients with functional dysphonia treated with the proprioceptive-elastic (PROEL) method. Journal of Voice, 32(2), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvoice.2017.05.018

McKinney, J. C. (1994). The diagnosis and correction of vocal faults. Nashville, TN: Genevox.

Sale, J. J. (2021). Effects of power posing on collegiate singer confidence in vocal sight reading. Unpublished manuscript, University of Kansas.